How Emily Warren Roebling Stepped in to Complete the Brooklyn Bridge

When debilitating illness struck her engineer husband, she became the person who made the historic project possible.

Hulton Archive / Getty Images

In May 1883, 39-year-old Emily Warren Roebling drove the first carriage across the just-completed Brooklyn Bridge, in advance of its "official" opening on the 23rd when schools and businesses were closed for the occasion and President Chester Arthur would make a crossing. Roebling's passengers were her teenaged son, John, and a live white rooster accompanying them as a symbol of progress and prosperity. She herself was much more than a symbol, as the cheering workers who raised their hats to her knew well. For the past decade, she had linked the bridge’s chief engineer to the workers who raised it over the East River — and Emily was as essential to its completion as the steel-wire cables that suspended it. How did a young mother and socialite become a historic bridge’s backbone? That’s quite the story.

Portrait of Emily Warren Roebling (1896) by Charles-Émile-Auguste Carolus-Duran (French, 1838-1917). Oil on canvas / Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Paul Roebling

An Unusual Education

Born in 1843 to Phebe Lickley Warren and Sylvanus Warren, a New York State assemblyman, Emily was the second-youngest of 12 children. As a teenager, she left her childhood home in Cold Spring, New York, to attend Georgetown Academy of the Visitation in Washington, DC, where she studied science, mathematics, history and French. (She also received instruction in housekeeping and needlework, subjects widely considered much more suitable for young ladies at the time.)

In early 1864, when Emily was 20 years old, she visited her beloved older brother Gouverneur, then a Union Army commander. She attended a soldiers’ ball and made the acquaintance of young Washington Roebling, a second-generation civil engineer whose father, John, was designing the Brooklyn Bridge. Less than a year later, Emily and Washington were married at a ceremony in Cold Spring.

Building a Life

The newlyweds soon sailed for Europe, where they traveled the continent so that Washington could conduct research on the “newly developed pneumatic method of sinking caisson foundations” that was revolutionizing bridge construction — and would aid him in work with his father on the East River project. Their son was born in Germany in 1867, and the Roeblings returned to the States as a family of three with extensive plans on the horizon.

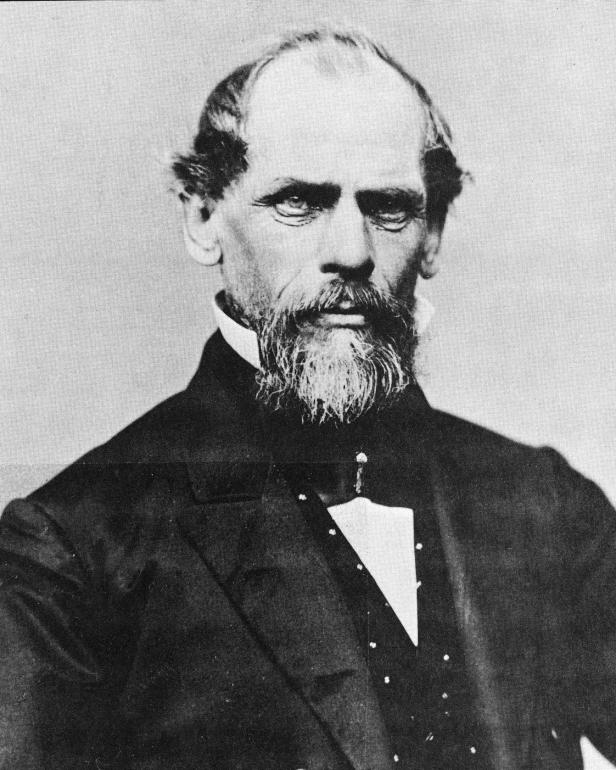

Kean Collection / Getty Images)

Washington Roebling, Emily's husband.

Tragedy Strikes Twice

Those plans changed for the first time in June 1869 when John Roebling the elder (below) was standing on a riverside dock plotting the bridge’s location. An arriving ferry crushed his foot and a tetanus infection developed in his wounds. He died less than a month later. Washington was named chief engineer of the bridge project in his father’s place, and construction began under his supervision on January 3, 1870.

Photo by Kean Collection / Getty Images

John Roebling, Emily's father-in-law, who died before construction of the Brooklyn Bridge could begin.

Fate threw the Roeblings for a second loop when the caissons that Washington had studied so diligently in Europe nearly killed him. Working with those massive, watertight chambers — which were sunk beneath the river and filled with compressed air so builders could construct the foundations for the Brooklyn Bridge’s two now-iconic towers — was incredibly dangerous. Three workers died of what was then called “caisson disease” (also known as "the bends," when gas bubbles form in body tissues during decompression) before their chief engineer developed the same sickness, in 1872. Washington suffered two decompression-related attacks, and the second confined him to his bed, making it impossible for him to supervise construction in person.

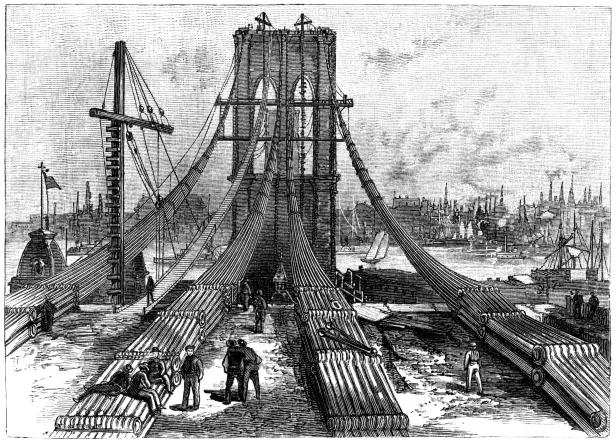

Ann Ronan Pictures / Print Collector / Getty Images

Cable anchorage leading to one of the Brooklyn Bridge's two towers.

Emily Engineers the Bridge

With Washington partially paralyzed and initially unable to see or hear, Emily became his eyes and ears. Although her husband retained the title of chief engineer — a title she fought for him to keep over the course of the next decade — she was the one who served as de facto project manager, making daily visits to the building sites, attending board meetings and negotiating with local politicians. She studied tirelessly to transform her once-amateur interest in her husband’s civil-engineering work into practical working knowledge of everything from materials and stress analysis to curve calculations and cable construction. (She had a significant start, mind you; she had not sat idle on her working honeymoon abroad.)

Bettmann / Getty Images

Groups of officers like this one might have reported to Emily, the bridge's "surrogate" engineer.

Though Emily had to strike a delicate balance between asserting her expertise and authority on the project and maintaining the position that her husband was and should remain its chief engineer, her contribution to the bridge’s creation was no secret in the city. On the front page of the New York Times on May 23, 1883, a piece on “Mrs. Roebling’s Skill” bore witness to her work: “As soon as Mr. Roebling was stricken with that peculiar fever which has since prostrated him, Mrs. Roebling applied herself to the study of engineering, and she succeeded so well that in a short time she was able to assume the duties of chief engineer,” it read. No mere note-passer or mouthpiece was Emily: “When bids for the steel and iron work for the structure were advertised for three or four years ago,” the article continued, “it was found that entirely new shapes would be required, such as no mill was then making. This necessitated new patterns, and representatives of the mills desiring to bid went to New York to consult with Mr. Roebling. Their surprise was great when Mrs. Roebling sat down with them, and by her knowledge of engineering helped them out with their patterns and cleared away difficulties that had for weeks been puzzling their brains.”

Bettmann / Getty Images

At least 20 workers were killed in the Brooklyn Bridge's construction, and many more suffered from the same decompression symptoms that affected Washington Roebling.

Emily Appears in HBO's 'The Gilded Age'

Courtesy of HBO

Liz Wisam portrays Emily Roebling in the second season of HBO’s "The Gilded Age," the hit series that chronicles clashes between New York City’s old guard and the new money set (and old and new ways of thinking) in the 1880s. Seen here in a costume that’s delectably similar to the real Emily Roebling’s garb in her 1896 oil portrait by Charles-Émile-Auguste Carolus-Duran, her television-drama equivalent differs from her in a few significant ways: “Emily Roebling” is separated from her husband, who is in Newport, Rhode Island; the real Washington Roebling could see the bridge’s progress through a telescope from his home in Brooklyn Heights. The fictitious character is adamant that the world not know of her role in the bridge’s construction; the real Emily wasn’t quite so invested in subterfuge.

Feast Your Eyes on Design Details and Historic Locations From HBO's ‘The Gilded Age’ 30 Photos

HGTV took a master class on Victorian interiors and trends from the designers bringing 19th-century New York City to life on HBO's ‘The Gilded Age.’ Ready for the most lavish behind-the-scenes tour we’ve ever done? Watch the interview and come on in.

Mrs. Roebling’s Life Beyond the Bridge

After her momentous carriage ride across the bridge with young John and the white rooster, Emily Roebling moved with her family to Trenton, New Jersey, where she supervised construction of their house, because of course she did. Though Washington was unable to join her abroad, her own travels were extensive, and she both attended Czar Nicholas II’s coronation in Russia and was presented to Queen Victoria at court in England. She crisscrossed the United States giving lectures for the Federation of Women’s Clubs and became known as a vocal proponent of women’s equality. In 1899, at the age of 55, she sat for exams and earned a Women’s Law Course certificate from New York University.

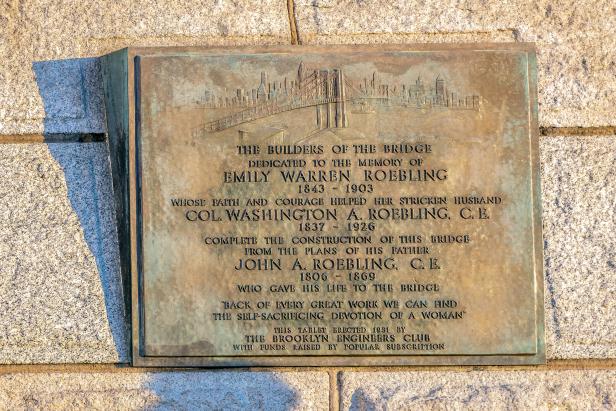

Universal History Archive / UIG / Getty images

In 1950 and 1951, the Brooklyn Engineers Club installed plaques at the base of the Brooklyn Bridge recognizing the efforts of all three Roeblings; Emily is recognized first, a detail she would have found fitting. As she wrote in an 1898 letter to her son, “I have more brains, common sense and know-how generally than have any two engineers, civil or uncivil, and but for me the Brooklyn Bridge would never have had the name Roebling in any way connected with it!”

Florin Cnejevici

As the New York City congressman Abram Hewitt put it at the bridge’s opening ceremony, “The name of Emily Warren Roebling will … be inseparably associated with all that is admirable in human nature and all that is wonderful in the constructive world of art.”

.-Battle-on-the-Beach-courtesy-of-HGTV.-.jpg.rend.hgtvcom.196.196.suffix/1714761529029.jpeg)